Music From the Air is Old, He Says

Frank E. Miller, the Theremin Controversy and the Audion Electric Organ 1915-1932

In Albert Glinsky’s (2000) Theremin: Ether Music and Espionage, a controversy is described concerning Leon Theremin’s early days in the USA involving Frank E. Miller. The day before the first public exhibition of the Theremin at the New York Metropolitan Opera House [31st January 1928], a number of newspapers in the city reported that an American, Frank E. Miller, disputed Leon Theremin’s claim to have invented his instrument. The New York Post (‘N.Y. Man Says He Made Music Wand’), New York Sun (‘Music From [The] Air is Old, He Says’) and New York American (‘Both Rivals Claim to Own First Patent’) ran stories outlining Miller’s claims, followed by a New York Times article (‘Disputes Invention of ‘Ether Music’) on the day of the first Theremin concert. Glinsky described Miller as an ‘ear, nose and throat specialist’ who had ‘performed maintenance on the throats of many Metropolitan Opera stars and, as a singer himself, had made a study of the voice, which led to his own voice production method — “Vocal art-science”’. Miller claimed he had ‘discovered the principle’ on which the Theremin instrument worked in 1910, and patented an apparatus based on his idea in 1921. In the New York American story, Miller stated

Acting under the advice of my patent counsel … and merely to protect my interests, I have been compelled to notify Mr. Theremin that his instrument is an infringement upon my patent entitled: 'Electrical System for Producing Musical Tones' which was issued to me by the United States Patent Office, under date of April 26, 1921, No. 1,376,228.

However, Glinsky suggested Miller’s patent, filed on 18th March 1915, was ‘a simple device for generating tones from an audion bulb [vacuum tube]’ that had little to do with Theremin’s ‘hands-off’ space control method of performance, had no timbral control, no volume modulation, and did not use the heterodyne process where two inaudible high frequency vibrations are made to act on each other to produce a single audible frequency of variable pitch (a technique pioneered in radio technologies).

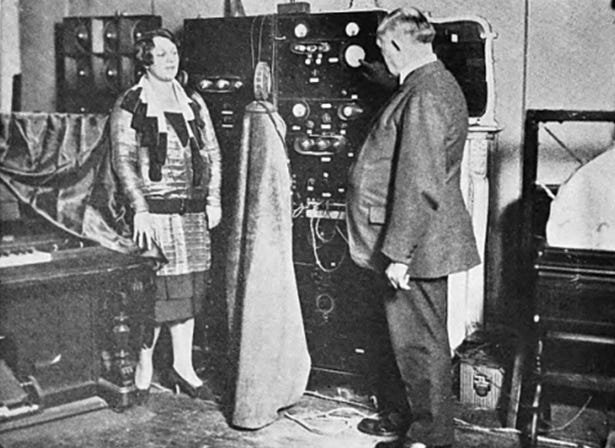

Glinsky outlines how on 29th January, the day before the story broke, Miller invited newspaper reporters to his home studio to demonstrate his instrument. As I will outline later, this instrument was of a different, more sophisticated design to that patented in 1921 - a two-octave electric keyboard that appears to have had similarities to Hugo Gernsback’s 1926 Pianorad instrument. Glinsky noted that the New York American reporter observed the instrument appeared ‘akin to a descendant of the original typewriter’ combined with ‘modern radios’ (a description that could equally well have been used to describe the early Trautonium instrument in Germany). A month later, Glinsky observed that Theremin’s US patent was granted as a ‘method of and apparatus for the generation of sounds’ under patent number 1,661,058, with the examiners finding no conflict with Miller’s patent.

Reading this I felt there were a number of elements of this story that I wanted to look into, particularly concerning the nature of Miller’s initial patent, but also concerning what he by the mid-1920s called his ‘Audion Electric Organ’. However, I was also intrigued with the idea that Miller professionally was a medical specialist who clearly had an (amateur?) interest in emerging electrical technologies. Glinsky’s remark that Miller was ‘an eccentric’ seemed a little dismissive of his efforts, so I decided to look in more detail at Miller’s life and work.

Dr. Frank Ebeneezer Miller [1859-1932]

Dr Frank E. Miller was born in Hartford, Connecticut on 12th April 1859, and studied at Trinity College there until 1881, and then graduated from the New York College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1884, age 25. He worked as a medical and surgical interne at the New York Charity and St. Francis Hospitals, and from 1886-89 he became a sanitary inspector for the New York City Board of Health. He then served as an assistant under a number of professors in the New York Polyclinic, the Vanderbilt Clinic, the New York University and the Post-Graduate Hospitals, and began specializing in diseases of the throat. He took on the role of laryngologist at the Metropolitan College of Music in 1890. In the 1890s he began his private practice as an ear, nose and throat specialist. In 1906 he was appointed visiting physician to the New York Hospital, and practiced at a number of medical institutions including the Vanderbilt and Bellevue Hospitals, and continued as a consulting physician at the St. Francis and St. Joseph’s Hospital in New York until his death in 1932.

Miller had a particular interest in music and the voice, and sang for a time as solo tenor in the Glee Club at Trinity College, and was later first tenor in the choir of the St. Thomas Episcopal Church in New York. His medical and musical knowledge came together in his scientific study of the voice, and in a number of books.

1910 - The Voice: its Production, Care and Preservation - the book’s introduction states that Miller was ‘one of the leading New York specialists on throat, nose and ear’ and was ‘physician to the Manhattan Opera House, Mr. Oscar Hammerstein’s company’, and ‘[t]o expert knowledge of the physiology of the vocal organs’ he added ‘practical experience as a vocalist’. The book balanced the physical and temperamental challenges faced by vocalists drawing from scientific knowledge and ‘long observation and experience’.

1912 - Miller-Merton Vocal Atlas: Designed for Teachers and Students of Teaching and Speaking - a teaching aid enabling students to ‘readily and clearly to understand the teacher’s instruction and all references to the vocal organs and their regions, here shown with such uncommon simplicity’.

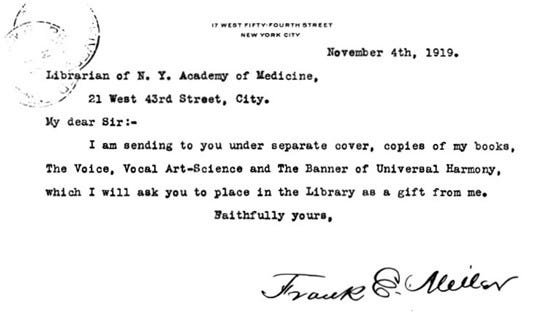

1917 - Vocal Art-Science and its Application - in his introductory comments, Miller outlines problems with human voice analysis, lamenting the lack of accurate measuring and recording devices ‘which permit exact study and analysis of tone’. He then explains in detail why existing phonograph technology imperfectly transmits sound-waves through a loss in overtones. Although unmentioned here, alongside his voice studies Miller had since 1910 been working on technological developments to aid in his study of the voice, and to address the issues identified - in the process he began to consider the musical possibilities of his work.

1919 - The Banner of Universal Harmony - this is a strange concoction of spiritualism, Masonic iconography, acoustics, geometry, physics and post-WW1 idealism in the mapping out of a theory of international ‘brotherhood’. This esoteric work can best be explained by the fact Miller was also a Mason, a Knights Templar, a member of the Mystic Shrine, and of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks.

The technological developments related to sound and acoustics mentioned above had resulted by 1921 in five U.S. patents held by Miller; several of these shared a fundamental approach that transferred the structures of the human ear to technological solutions [dates below are original submission dates followed by patent conferment dates]:

Voice and Sound Recording Machine (1915/1916)

‘My invention relates to the improved sound-mechanism having features applicable both to the recording of sound and to the reproduction of sound from a record or other known means … The object of my invention is to provide functioning parts for overtones and the many peculiar refinements of sound as well as for fundamental tones.’

Cusp Diaphragm Mechanism (1916/1917) and Cusp Diaphragm Construction (1918/1919)

‘The invention relates to [a] sound functioning mechanism, specifically of the type in which a train of electric variations reproduce sound vibrations … More particularly, my invention relates to electromagnetic telephones, particularly to the receiver mechanism but generically also to the transmitting mechanism … [it] bears a close relationship to the organic mechanism of the human ear …’.

Fixed Selective Stethoscope (1918/1918)

‘The object of my invention is to provide for the making of soundings upon the body of a patient under conditions of no discomfort to the patient and of convenience to the physician … I contemplate the location of a plurality of electrical transmitters positively positioned relatively to the desired parts of the human anatomy … I further contemplate suitable circuits, receiving apparatus and selective control means whereby the receiving apparatus may be actuated by any set of one or more of the specially located transmitters’.

Electrical System for Producing Musical Tones (1915/1921)

‘My invention relates to a system for producing musical sound. The object of my invention is to produce pure toned musical sounds of any desired frequency by exciting an audion in response to electric pulsations or oscillations of a predetermined frequency controlled by the selection and proportioning of capacity and inductance in the exciting circuit and independently of the frequency of an alternating current electric generator … My invention differs from what has been done heretofore in that I employ an exciting circuit for the audion which in itself is equivalent of a musical sound and which must reproduce its own charcteristic whenever operatively energized by a suitable source of electric energy … A further object of my invention is to employ an audion under the control of a plurality of exciting circuits, each having a characteristic frequency capable of reproducing one of various selected musical sounds, for example, a plurality of circuits characteristic of the chromatic scale … I propose to employ an electrically operable sounding member such as an electric horn for actually producing the musical sound, or rather for translating it from an electric vibration into an audible mechanical vibration’.

The system described by Miller has a feature unremarked on in newspaper coverage of the later dispute with Leon Theremin. That is, the method of playing or performing on this device in the patent is in effect a multi-track electric sequencer modelled on a traditional music box. The cylinder (K) in the bottom left of the patent diagram is connected to an electric motor for constant speed rotation. On this cylinder are raised areas - each of these when making contact with the ‘contact pieces T’ close a circuit and sound a musical note. There are eight ‘T’ pieces, so it is possible to trigger eight notes simultaneously for polyphonic playback. However, in later coverage, Miller’s instrument is described as a two-octave keyboard instrument, where instead of a sequencing cylinder, piano style keys are used to close circuits to sound musical tones. The clear suggestion here is that Miller’s 1921 patent, based on a 1915 set of ideas, by 1928 did not represent how his instrument had evolved.

In the period after the 1921 patent, Miller continued with his interest in electrical and radio technologies. In 1925, alongside his long-term technical collaborator Robert M. Lacey, he established a radio station in New York (2XV) - as yet I have found no information on the broadcast activities of the station.

In 1926, a ‘sturdy’ loudspeaker was placed on the market in the USA that drew from three of Miller’s patents - the Pausin Octacone.

By 1927 Miller and Lacey had established the Frank E. Miller Radio Corporation, presumably to explore the potential for marketing their own inventions. A 1925/1927 US patent for a ‘Push Pull Reproducer’ [a loudspeaker also known as the Miller Diaposon Diaphragm] was assigned to Miller and Lacey as the Frank E. Miller Radio Corporation of New York.

Before moving on, it is worth briefly mentioning that Miller was also active as a songwriter and lyricist in the 1920s. I have found several copyright entries in Library of Congress records for musical compositions. For example, the 1920 song ‘Panaethesia’ with words and music by Miller, and 1925’s ‘Swanee Cabin Home’ - a fox trot, with words by Miller and music by James Amoroso. Related to this, in the early 1920s Miller even seems to have offered a ‘Song Poem Service’ that ‘[w]ill write you a song poem on any subject. Also criticise and revise song poems. Prompt and efficient service always.’ Additionally, in the early 1920s he wrote a play - The Goal - about the fall of Lucifer, apparently inspired by a trip to the Grand Canyon in 1921.

The Miller v Theremin Patent Dispute 1928

On 31st January 1928 the New York Times reported that Dr. Frank E. Miller claimed he was the inventor of ‘ether music’ and that ‘a variation of his fundamental discovery was used by Professor Leon Theremin … in his sensational recitals’. Leon Theremin denied this, but ‘accorded to Dr. Miller and others recognition of their pioneer work in musical acoustics’, and had already been to Washington to ‘register patents on his ether musical instrument, which he calls the Thereminophone’.

Miller indicated in the story that he had obtained his 1921 patent by ‘winning in the lower court and twice on appeal when Dr. Lee de Forest claimed inventions controlling the field of electrical music’. He explained that he had not made a great deal of progress on his own instrument since 1921 due to lack of funds. However, he had developed a two-octave keyboard instrument that he demonstrated at his home and in a Carnegie Hall studio. Miller stated ‘I do not intend to make any trouble but I want my rights recognized. I admire the great skill which has been shown by Professor Theremin, but he has done nothing which has not been covered by my fundamental patents’. A few weeks later in the Yonkers Statesman [3rd March 1928] Miller indicated that principles in his patent were used in

an instrument known as an ‘Audiometer’… manufactured and sold by … Western Electric under a non-exclusive license which I granted them … (reserving, however, all musical instrument rights in that license) … The Audiometer produces pure, fundamental tones or notes of any given frequency from below audibility to above audibility, and is therefore extremely useful to physicians and others in testing individual hearing capacity and for other purposes. Such an instrument, however, is not strictly speaking a musical instrument.

Miller then provided more information about his original musical instrument and its public visibility in the years of his patent dispute with Lee de Forest.

The original model of the musical instrument constructed by me and covered by this patent was for a long time used in the United States Patent office and in the courts as evidence in the [de Forest patent dispute] … This instrument gave most wonderful organ-like tones and was readily adaptable to augment and supplement an orchestration, because it gave out peculiarly high and low notes impossible of attainment by any other known musical instrument. Some of my associates have … been planning to produce a large-scale instrument of this type, capable of taking the place of the extremely expensive church and auditorium organ of the conventional design.

Soon after, Musical Advance magazine [March 1928], that had often reported favourably on Frank E. Miller’s musical activities over the years, published a quite remarkable, hyperbolic but also prophetic defence of Miller’s work. So far I have been unable to find who the author was, but the article appears to have been the last part in a series on the human voice in music. The article titled ‘Reducing Radio to the Exact Formula Which Produces Human Voice Tone’ looks to the future of music-making while meanwhile fighting Miller’s corner in the Theremin dispute. The article begins

Very soon the whole world will be listening to music originating in a box-like cabinet standing in a quiet room wherein only a single operator sits at an organ-like keyboard, entirely devoid of strings, such as are the basis of piano music, or connected in any way with pipes, the source of organ harmony. This operator by manipulation of the keys before him, manufactures the music that mimics in faultless perfection the combined instruments of a great symphony orchestra. And there is nothing more to it than an audion tube to represent every instrument which it is desired to imitate. The magic of the thing is the electron, that vital spark that is light, heat, energy, color and tone. No human eye has ever seen an electron, but it is the power that produces the marvelous results achieved by the invention of Frank E. Miller of New York, and which he calls, in his patent papers, an audion electric organ [N.B. I have yet to find this term in Miller’s patents]. With it he produces any sounds desired and in any volume. They are created by radio and the device is sure to become the most vital force in the new order of radio broadcasting.

There then follows a report of a discussion that took place in 1925 on board the White Star steamship Majestic involving Miller, the British conductor Sir Henry Wood and other passengers. Musical Advance reports this meeting in some detail, indicating Frank E. Miller made wildly extravagant claims for his instrument … as did others in the 1920s and 30s writing about the potential of their new electronic instruments.

[He] explained to Sir Henry Wood and the others present the wide range of action possible with the [Miller Audion Electric Organ]. It is possible, for instance, for one operator to supplant an entire orchestra, such as that of the Metropolitan Opera House, and to create the full score of the most elaborate grand opera, every tone of every instrument being produced in exact imitation of the actual instrument … with the faultless perfection of an instrumental orchestra playing under the guidance of the baton of a master conductor … If for instance thirty-two instruments are the fewest number possible of interpreting the score of a grand opera, then there must be thirty-two audion tubes, one for each instrument. And each audion rendered by its subdivisions capable of producing each note of whatever instrument characterized by its own special harmonies. As the operator at the keyboard depresses a key … each action opens and closes a circuit and controls the electrionic (sic.) force within one of the audions with which it is connected by copper wires … Every note possible of production by any instrument in the hands of a musician may be duplicated with exact precision by the Radio Organ …

The article then moves on to provide further details of Miller’s work on electrical music since 1909.

[Dr. Miller] is not a radio engineer. He is the conceiving artist who tells the engineer [Robert M. Lacey] how to do it … [his] method of reaching results has been to follow the principles of sound production that are found in the human throat instrument, with its accompanying resonators, and adapting audion tubes to take the place of the mechanism that exists by nature in every human throat … The Miller discovery is far more elaborate [than Leon Theremin’s instrument], enabling the operator, with the aid of his stabilising scaled audiometer … to heterodyne beat notes dynamically and kinetically with variable frequencies to any degree desired to produce delicacy of tone and proper harmony [N.B. this suggest by 1925 Miller’s instrument had adopted a heterodyne method that contradicts Glinsky’s critique of Miller’s instrument]. This was demonstrated by Dr. Miller, as long ago as 1909 and again in 1911 at Carnegie Hall, New York, by Robert M. Lacey, the radio engineer who, under the personal direction of the inventor, built a machine that did the work. This particular apparatus for five years was one of the public exhibits set up in the Bureau of Standards and Patents in the Patent Office in Washington, D. C., where anyone might inspect and study it. It had at that time been granted a patent by the United States Government, which is still in force, therefore the Theramin (sic.) device is an infringement.

The Musical Advance article then attempts to identify the superiority of Miller’s instrument in comparison to Theremin’s:

One tremendous difference between the electrical music box that is operated by Professor Theremin and the Radio Organ of Dr. Miller’s creation is that the first named produced but one note at a time, while the Radio Organ will produce, in perfect harmony, every note of a great orchestra of one hundred or more instruments, with every gradation of tone and timbre, singly, or together in harmony. This is not theory; it is fact. For it has been done and done to the satisfaction of the United States Patent Office. [The] Miller Radio Organ is also possible of adaptation mechanically through the use of perforated paper rolls … [but] Dr. Miller does not intend to make use of his invention for the disturbance of conditions and the elimination of the human orchestral bodies … [He] dismisses from his calculations commercial plans for the utilization of the device, being content that he has added his little bit to the sum total of human knowledge and deriving his pleasure from the achievement …

It may be the case that Miller had no great intentions of developing his work further in commercial terms, however in 1930 Miller was awarded a further patent on his Audion Electric Organ from an application filed on 18th June 1925 - around the same time that he discussed his instrument with Sir Henry Wood on the Majestic. This was titled ‘Electronic Tone Producer With Universal Audion’ and was an update on his earlier 1921 patent. Miller wrote

My invention relates to a system for producing musical sounds and tones, and also for use in testing the individual ear capacities for any desired purpose … The general basis and principle of my invention has been covered in Patent No. 1,376,288, dated April 26, 1921, on an Electrical system for producing musical tones, and my disclosure herein is a refinement and adaptation of said … patent.

Miller shows ‘typical key contact connections’ in his diagrams to allow for keyboard performance, while still referring to the possibility of using other means, such as a ‘revolving disc contact’ method to trigger musical tones. He also emphasises that his instrument can use a single vacuum tube that contains ‘a predetermined number of grids, each grid connected to a separate circuit’ that will also have ‘means for adjusting the impedance of each said circuit’, with the tube having ‘a single plate by means of which the effects produced by the grids co-acting with the filament’ would be ‘integrated to produce a chord of music or sound in a loud speaker’. A further patent, applied for on 5th November 1928 (a few months after the Theremin controversy) and awarded in 1931 - ‘Electrical System for Producing Musical Tones’ - further helped Miller refine his instrument so that it could ‘produce chordal music … with the use of only one reproducing unit or loud speaker’. However, just over a year later Frank E. Miller became ill, and died on 15th April 1932. By this point many others had begun to experiment with electronic instruments, particularly keyboard based devices, and Miller appears to have soon been forgotten despite his very early innovations in designing and constructing [in collaboration with Robert M. Lacey] an electronic musical instrument.