The aim of this article (and the one that follows) is to outline Hugo Gernsback’s role in propagating interest in electronic music through his writing and publishing activities, as well as two early electronic music instruments - the Staccatone and Pianorad - that he developed with an engineer collaborator, Clyde J. Fitch . Although both of these instruments are often mentioned in passing in electronic music histories, their impact or reach is perhaps underplayed. That is, not only were they read about in Gernsback’s magazines and heard on his New York radio station WRNY in the 1920s, but they also garnered national and international press coverage, in some cases in features that reprinted large sections of the original technical articles that appeared in Radio News.

Hugo Gernsback was born Hugo Gernsbacher in Luxembourg in 1884, and became fascinated with electricity as a 6 year old when given an electric doorbell to play with as a birthday present. He went on to study at the Rheinisches Technikum [Rhine College of Technology) at Bingen, Germany where he developed an improved dry battery. He emigrated to the USA hoping to market the battery there, but as manufacturing costs for the battery proved too great to make a viable profit, he instead found a job as an electrical engineer with a storage battery manufacturer, Emil Grossman. Soon after he formed the Electro Importing Company to make available European electrical equipment to US electrical experimenters, and in 1906 made a 'spark' radio set available for purchase that could transmit and receive signals. The company published a mail order catalogue that also included educational articles, and in 1908 Gernsback introduced Modern Electrics magazine which was the first magazine covering electronics and radio in the world, with news and articles on electrical theory and construction matters. In 1909 he founded the Wireless Association of America at a time when the number of amateur radio enthusiasts in the country was rapidly increasing.

From this point onwards Gernsback's efforts and business interests moved towards writing and publishing. He established Modern Electrics in 1912, and then in 1913 established a more ambitious publication, The Electrical Experimenter (eventually becoming Science and Invention in 1920 that ran until 1931).

In 1919 he founded the first US magazine purely focused on radio - Radio-Amateur News - that became Radio News in 1920.

Practical Electrics, a technical journal that included short stories, was also introduced in 1920. In 1924 it was retitled The Experimenter with stories in a serial format. In April 1926 he revised this magazine again, now with an emphasis on the emerging genre of scientific or science fiction, and renamed it Amazing Stories.

As Radio-Electronics [November 1967 p. 58] later reported in Gernsback's obituary,

Science fiction had appeared regularly in all the Gernsback magazines (quite a bit of it written by Gernsback himself) and a little was published in other magazines, together with weird stories and fantastic fiction. But [Amazing Stories] was the first attempt at a magazine devoted entirely to true scientific fiction. Its success stimulated dozens of others into being. All, however, look back to Gernsback as the First Cause, and he is unanimously acclaimed the Father of modern Science Fiction.

In 1929 after his publishing company ran into financial troubles, his magazines were sold to other owners. However, he immediately established new magazines including Radio-Craft (eventually Radio Electronics by 1948), Television News, Short Wave Craft and Sexology (one of a number of biomedical publications he published over the years).

Massie and Perry (2002) summarise Gernsback's contribution in this period as a writer and contributor to the magazines he published, observing

As a writer, not only did Gernsback contribute editorials and articles in his radio magazines, but he also wrote other works significant to radio. In 1922, for example, his book Radio For All … covered general principles of radio, how to read a radio diagram, the Radio Act of 1912, and much more that would initiate the beginner in the field … Beginning in 1930, Gernsback was the editor [with Clyde J. Fitch as managing editor] of a three-volume series called the Official Radio Service Manual that had a complete directory of all commercial wiring diagrams of receivers … Gernsback was a key promoter of and motivating force in the growth of early radio … Because he had the largest audience [through his publications], he was clearly one of the most influential figures in promoting radio inventions, innovations, and involvement.

Radio-Electronics [November 1967 p. 58] noted

Altogether, Gernsback published more than 50 magazines in the technical, experimental, biomedical, aviation and other fields … the number of books he published cannot be estimated accurately, but runs into the hundreds.

From his first book, The Wireless Telephone (1908) and his first serialised science fiction writing published in book form as Ralph 124C 41+ (1911), Gernsback attempted to predict technological futures extrapolating from emerging innovations with a fertile imagination that often proved accurate. Massie and Perry (2002) suggested Gernsback's motivation in encouraging invention and innovation was based on a commitment to scientific excellence.

He published the works of highly regarded experts in radio and electronics, and critiqued and criticised scientific inventions that he felt were flawed or needed improvement. This striving for scientific excellence was probably the chief factor in proving so many of Gernsback's predictions to be prophetic., first in the radio and electronics fields and later in his prognostications about travel to the moon.

There was no area of technical invention that he didn't have an interest in, and as a result over the years his thoughts regularly concerned electrical music. As noted, he was directly involved in the development of two electronic musical instruments in the 1920s - the Staccatone and Pianorad - with Clyde J. Fitch. He also promoted the efforts of others working in the field, including Lee de Forest who he provided a popular platform for in 1915 [Electrical Experimenter [December 1915 p. 394-395]] in an article about his ‘Audion piano’, and also looked back to the technical achievements of Thaddeus Cahill. In 1919 in an Electrical Experimenter editorial 'Electric Music', he considered what the future held for electrical music.

Gernsback in looking to the future of musical instrument design suggested

… as our musical tastes become more refined, still better instruments will become necessary and highly desirable … The field of purely electrical music has hardly been touched. Some years ago an American inventor [Dr. Thaddeus Cahill] produced the Telharmonium. This was one of the earliest and best attempts at pure electrical music … Another more recent attempt was the pure electrical music discovered thru researches of Dr. Lee de Forest. He used his Audion bulbs in connection with a telephone receiver, and obtained beautiful flute-like tones of the greatest purity. The two devices … necessitated the use of a telephone receiver to translate the electrical impulses into sonorous vibrations, and this is a great disadvantage, for it ties us to a thin diafram, which in itself cannot produce the very purest tones obtainable … it is possible to obtain a single pure note, it is a different matter where several pure notes in different octaves are to be reproduced simultaneously.

Gernsback goes on to suggest instead the use of a 'thermo-telephone' where a platinum wire vibrates in unison with electrical vibrations, and imparts 'impulses to the surrounding air', and vibrating electromagnets that produce music through the vibration of their 'entire structure'. He observes 'There must be many other ways of producing vibrations in a vacuum tube which can be translated into an electrical current, thus producing music'.

In 1922, Gernsback's Science and Invention [October p. 565/606/608] retrospectively reassessed the Telharmonium with an article 'Radio and the Telharmonium' by Robert Stewart Sutliffe. Sutliffe reported that

About 1908 the promoters of the Telharmonium lost over $1,000,000 in an effort to introduce commercially what proved a great artistic success, and for which there was a strong public demand. … [Dr. Thaddeus Cahill] demonstrated that he not only had the formula for making musical sounds, but the machine to manufacture them as well.

Unfortunately the business plan to distribute (stream?) Telharmonium music to subscribers through overground or underground telephone cables proved technically and financially unachievable in the first decade of the twentieth century. However, Sutliffe noted

The question now presents itself of the possibilities of the Telharmonium in conjunction with radio. We show herewith an illustration of the elementary working of the Telharmonium, and also how it could be used in connection with a radiophone broadcasting station.

Perhaps it was a combination of Lee de Forest's - a friend of Gernsback's - earlier work on his 'Audion piano' and the broadcast distribution model pioneered by Thaddeus Cahill that led Gernsback and Clyde J. Fitch to design and introduce a new electronic musical instrument, the Staccatone, that would soon be heard on Gernsback's New York radio station WRNY.

The Staccatone

In March 1924 in Gernsback's Practical Electrics magazine, Staccatone collaborator Clyde J. Fitch wrote a technical article [p. 248-9] outlining details of the new electrical musical instrument.

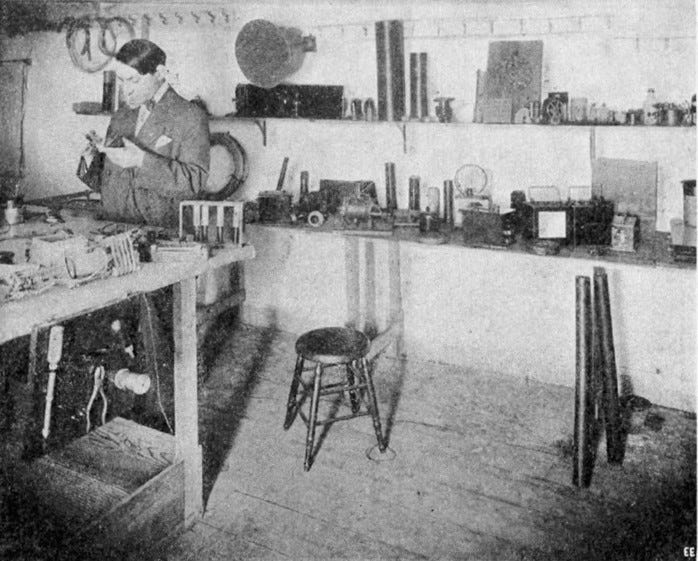

Usually Fitch is briefly mentioned as a co-inventor of the Staccatone in electronic music histories, but nothing is added concerning his life and career, so it seems important to fill in these details. Fitch was associated with Gernsback from the early 1920s; he worked in the Gernsback laboratory designing radio circuits and radio instruments, contributed magazine articles to his publications, co-edited books with Gernsback as well as writing his own, gave technical lectures on WRNY radio station, and was associate editor of Electrical Experimenter and Everyday Mechanics magazines. By the late 1920s he was particularly renowned as a loudspeaker expert, writing a book How to Build Modern Loud Speakers (1927). Fitch later worked with IBM from 1933 at the General Products Division Laboratory for over 30 years and when he retired he was said to have held the record for the most inventions made while working at the company. He was one of the original 8 honorary IBM fellows, an award given in recognition of his outstanding record of continued innovation and achievement.

In Fitch's article, the Staccatone is described as Gernsback's idea that he then developed, and he reported that it was first introduced to the public when broadcast on the WJZ radio station in November 1923. The instrument was named the Staccatone due to its staccato-like flute sounds that were 'pleasing to the ear and very clear, the notes at the same time being very pure'. In outlining the technical basis of the instrument, it is clear that it uses principles pioneered by Lee de Forest around 1915, and tone generation is achieved in a manner similar to Tournier's 'orgue électrique', Termen's Theremin, Martenot's 'ondes musicales' and Djounkovski's 'Klingende Wellen'. Gernsback and Fitch's Staccatone featured a number of electrical switches through which to play the instrument monophonically with discrete notes/pitches. de Forest’s instrument had used a vacuum tube per octave and was also monophonic. Tournier's 1924 instrument used a piano style keyboard and a vacuum tube per note/pitch and was therefore polyphonic and a much more sophisticated device. The Staccatone’s simplicity was intentional as Fitch's article encouraged the radio enthusiast reader to build their own version of the instrument, with details of the circuit design and required components.

Fitch wrote

Has it ever occurred to you that the squeals and whistling noises which you hear in your radio set while trying to tune in to a distant station may be controlled so as to produce pure musical tones; and that with a vacuum tube, a few coils and condensers a simple musical instrument is easily made, on which any song or tune can be played?

The characteristic squeal rising in pitch from zero to a note beyond the limit of audibility is familiar to all of us. This range of frequencies runs much higher than can be obtained from any known musical instrument. If properly controlled we have a musical instrument that surpasses in tonal range any other musical instrument, and the note is exceptionally pure, practically free from harmonics. Of course, with several vacuum tubes harmonic chords could be played. With the single vacuum tube musical chimes and tunes can be played that are very pleasing to the ear when played alone or in connection with an orchestra. The experimenter will find much amusement in one of these musical oscillators, and if he is careful in tuning it he will find it in great demand by dance hall orchestras where novelties are the chief attraction …

The squeals heard in radio sets are caused by the interference of two waves of different frequency setting up an audible beat-note, and squeals are difficult to control, as the slightest change in the capacity of the apparatus, such as is caused by moving the hand near the set, will change the pitch of the beat-note considerably. As this system would be impractical for our purpose we shall use a vacuum tube connected so as to generate low or audible frequency notes which sound the same as the beat-notes heard in radio.

In July 1924 the Staccatone was demonstrated at the Rialto Theatre in New York, and regularly appeared playing an identifying signal for the WRNY network three times a day when it began broadcast on12 June 1925.

Originally the WRNY signal consisted of the first three bars of 'The Stars and Stripes Forever', and was played via an automated clock driven switch that was in effect an electro-mechanical 'sequencer'. A detailed description of the device (see below) appeared in Radio News [September 1925 p. 284]. However, by January 1927 it was felt that this signal had become over familiar and tiresome for listeners (and probably for WRNY workers). Instead, a new simplified Staccatone signal was introduced. The Washington Evening Star [5-1-1927] reported that

The staccatone, the peculiar flute-like instrument which has been transmitting an identifying signal from WRNY, New York, during lulls in the programs of that station, has been modified so that it now produces a sound exactly like that made by a cuckoo. Radio listeners who pass the 374 meter setting in tuning their receivers can instantly recognise WRNY by the unmistakable chirping.

The Pianorad

On June 12th 1926, at the first birthday celebrations of WRNY, Gernsback and Fitch demonstrated their new, improved electrical musical instrument, the Pianorad, for the first time. Radio News [November 1926 p. 493/603] featured an article by Gernsback that discussed the capabilities and construction of the new instrument that he had devised, and that was built in the Radio News Laboratories by Fitch; in the following December issue Fitch wrote an article 'How to Build "The Pianorad"'.

Gernsback wrote

This year marks the second centenary of the creation of the piano. There has been no radical development in the piano since except the advent of the player piano or mechanical piano. The Pianorad, which is played very much like the piano, by means of a similar keyboard, is a new invention. In this new musical instrument, the principles of the piano as well as the principles of radio are for the first time combined in a single musical instrument … The Pianorad has a keyboard like an ordinary piano, and there is a radio vacuum tube for each one of the piano keys. Every time a key is depressed, there is energized a radio-oscillator circuit which gives rise to a pure, flutelike note through the loudspeaker connected to the device. It is possible to connect any number of loud -speakers to the Pianorad if it is desired to flood an auditorium with its tones … The musical notes produced by vacuum tubes in this manner have practically no overtones. For this reason the music produced by the Pianorad is of an exquisite pureness of tone not realized in any other musical instrument. The quality is better than that of the flute and much purer. The sound, however, does not resemble that of any known musical instrument, the notes are quite sharp and distinct, and the the Pianorad can be readily distinguished by its music from any other musical instrument in existence. In the Pianorad one vacuum tube for each key is connected electrically with certain coils (inductances). Any number of notes can be played simultaneously. as on the piano or organ; unlike the piano, however, the notes can be sustained for any length of time … The loudspeaker arrangement makes it possible for an artist to play the keyboard while the music emerges, perhaps miles away from the Pianorad [as with the Telharmonium] … The instrument illustrated in this article has 25 keys and therefore, 25 notes. A full 88-note Pianorad has as yet not been constructed, but will be built in a short time. [This appears never to have been constructed]

Fitch in providing a construction overview Radio News [December 1926] outlined how

While it may appear to the reader at first sight that the Pianorad is a complicated piece of apparatus, this is far from the truth. It is true that 25 vacuum tubes are employed, and radio set builders know very well the amount of labor required to assemble a five -tube set. Consequently the Pianorad is no more complicated than five radio sets ; in fact, considerably less so because each tube in the Pianorad is wired like all the other tubes, whereas in a radio set the tubes are all wired differently.

Fitch then went on to indicate that the constructor should first obtain a radio console cabinet and adapt a beginners practice two-octave keyboard, and then outlined the full construction method of the audio oscillator circuits and how to tune individual vacuum tubes using small pieces of iron:

It is almost impossible to obtain fixed condensers of the exact capacities required to tune the circuit to a definite musical tone. Therefore, we connect across the coil a fixed condenser that gives a note rather near, but higher in pitch than the musical tone required ; and then fine iron wires, or for that matter any small pieces of iron such as nails, are placed in the center of the windings, where the core was originally. As the iron approaches the coil the pitch of the tone lowers. Perhaps the correct note is obtained with a piece of iron wire half way into the coil. Some means, therefore, must be devised to hold the iron in position.

In building the Pianorad it was found that the simplest method is to fill the center holes of the windings with modeling clay, and then stick the iron wires into the clay. In this way a very gradual change in pitch can be made and it can be held constant at any desired value.

For amplification Fitch described how the Pianorad featured

twenty-five loud-speaker units mounted on one sound chamber which opens out into a bell-shaped horn. Each unit was connected to its respective vacuum tube and switch on the keyboard. As adjustable units are used, the volume of each note can be regulated until all are uniform.

Conclusion

One of the interesting questions concerning the influence of the Staccatone and Pianorad is to consider their reach - how many of the readers of Radio News actually attempted to build these instruments? How many then performed with them? There are currently no clear answers to these questions. But how influential were they? Perhaps their importance is that through them, Gernsback and Fitch inspired the coming generation of US electronic musical instrument builders of the 1930s. What should be emphasised is that both of Gernsback and Fitch's instruments were covered nationally and internationally in the press (I have found many examples). Those who hadn't heard the instruments would have been aware of them, and they may equally have been inspired by the reports and technical details shared in the news articles. Many early radio listeners in the USA would obviously have been familiar with the sound of the instruments. The instruments had educational and inspirational value, even if they played no real role in the wider musical culture of the day - or at least not one that has been found in the research I've done so far. In the popular imagination, by late 1927, they were eclipsed by the arrival of the Theremin, and then perhaps became forgotten. Nevertheless they are usually noted as important developmental stepping stones in published electronic music histories. Gernsback appeared to have been aware of the overshadowing of his own efforts when writing about Lev Termen and the Theremin in Amazing Stories [December 1927 p. 825], and felt it necessary to emphasise his and Fitch’s earlier achievements.

As has often been said, fact is stranger than fiction. If, for instance, we had published a scientifiction tale whereby a musician, just by waving his hands in the air, without any physical contacts of any kind, could produce the most beautiful music imaginable, I know right well that we would have been inundated with protests that such a thing is a physical impossibility. Indeed, every scientist could have given you dozens of good reasons why such a thing would be entirely absurd, impossible, and just pure fiction. Nevertheless, in the current issue of Science and Invention, there is described the apparatus jnvented by L. Theremin, a young Russian who uses radio principles for his enthralling new kind of music.

In front of him stands a box containing certain radio instruments. From the top of the box issues a rod, while at the left hand of the box is a brass ring. Just by waving his hands in the vicinity of the rod and ring, Mr. Theremin produces the purest as well as the most beautiful kind of music that has ever been produced. The effect of the body capacity of the human being is responsible for the music and anyone can learn to play the instrument in short order, providing he knows music. The instrument gives forth flutelike or violin sounds of the most exquisite beauty.

A similar instrument, by the way, was used about two years ago, in my so-called Pianorad, an instrument using 24 radio vacuum tubes, which I operate by means of an ordinary piano keyboard, while the music issues from the loud speaker the same as does the music of Theremin. Both instruments are based upon the same principle, except where I use an actual keyboard, Theremin uses his hands, which now act as an electric condenser. Otherwise the principle of the two apparatuses is the same.

However, I do wonder how widely Gernsback's role in propagating electronic music is understood due to a wider interest in his many other activities and interests, particularly in science fiction, but also radio, television and space travel (among many other subjects).

In Radio Craft [March 1933 p. 521], in an update to his 1919 'Electric Music' editorial, Gernsback turned his attention to what was now called 'Electronic Music', reviewed his involvement in the field in the previous decade and a half, and predicted what electronic music developments he felt were soon to arrive.

ELECTRONIC MUSIC

A new type of radio instrument will make its appearance within the next few years. It will doubtless be sold by the millions, and it is well that all those now interested in radio should be prepared for what is coming. I refer to electronic musical instruments, whereby an entirely new type of music is produced that anyone, who has knowledge of music, can play. These instruments will be quite small, and so will take up little room; in most cases they will connect with your radio set so the music will issue from the radio loudspeaker. Others will be more elaborate: probably in the form of pianos or other furniture design, with amplifiers and loudspeakers incorporated in the instrument itself. These instruments will be played by means of the usual piano keyboard, or by touching a wire-string, or even by running one finger over a resistance, similar to the instrument for the first time described in this issue of Radio Craft. [the Trautonium]

Electronic music is not new - indeed, it was invented by Dr. Lee de Forest. The first public account of such an instrument appeared in my former publication, the Electrical Experimenter, of December, 1915, when Dr. de Forest wrote an illustrated article for me entitled, “Audion Bulbs as Producers of Pure Musical Tones.” … Due to the imperfection of vacuum tubes, at that time, nothing much came of the idea. Years later, in Practical Electrics for March, 1924, when vacuum tubes had been greatly improved, I described an instrument of the electronic music variety which I termed the "Staccatone." This instrument I played publicly for the first time in November, 1923, over WJZ of New York. The same instrument was also used in a theater, in April, 1924, when I loaned it to Dr. Hugo Riesenfeld, who had one of his musicians play it in the Rialto Theater in New York. So much for the history of electronic music.

Last summer, in Berlin, I witnessed the performance of the first commercial instrument, the "Trautonium," invented by Prof. Trautwein of Berlin. The Germans have made great headway in electronic music, and many of their instruments have already been exported to this country. I understand on good authority, that a number of American manufacturers are about to produce small and low-priced musical instruments of this kind, which may be used as an adjunct to any radio set; I am certain that we shall witness an avalanche of such instruments in the very near future …

Indeed, it is certain that electronic music will revolutionize the entire musical art, including the musical instrument field, during the next decade. The vistas opened to experimenters and serious constructors are tremendous … Entirely new musical effects will be produced which we cannot now foresee … which are sure to be perfected once a few real musicians get together with a few good technicians …

In Part 2 of this study I will consider the wider role played by Gernsback's publications, in particular Radio Craft in the 1930s, in the coverage of early developments in electronic music in the USA.