Painting Sound and Music [1]

Eric A. Humphriss, Rudolf Pfenninger and Graphical Sound in the Press 1931-1935

In my last post I wrote about John Mills and his 1935 book, A Fugue in Cycles and Bels, where he discussed the technological future of electrical music. He believed that the most practical way to make progress beyond the achievements of vacuum tube oscillator instruments - such as the Theremin and Martenot’s ‘Ondes musicales’ - was to explore the method of drawn sound on optical film soundtracks.

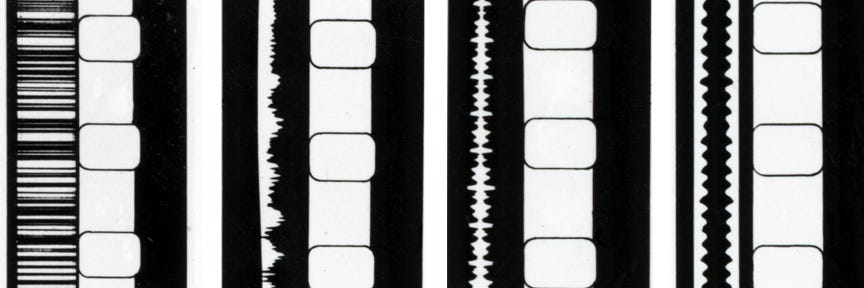

It was discovered in the 1920s that any shape or mark on the soundtrack strip next to the film image in the new film sound technologies would create a sound; not just the recordings of actors voices, music and sound effects, but also shapes and designs purposely drawn on the soundtrack. These markings, when light was projected through the film onto a photo-electric cell, created variable amounts of resistance in a circuit that could be amplified and converted (back) to sound through loudspeakers. Several different systems working on the same principle were developed.

Mills in looking to the future outlined how drawn sound techniques could be further refined;

The wave form of any desired complex sound may be constructed by accurate mechanical drawing. All that is required is to lay out each sinusoid [sine wave], making the height of its wave proportional to the amplitude desired for that component, and then to combine all these space patterns into a pattern for synthetic sound. This graphically constructed wave may then be photographed on a strip of film to produce a variable-area sound track. From this the synthetic sound can be obtained in the usual manner for such [recordings].

However, as I indicated at the end of my article on Mills, this technique - or very similar ones - had already been developed in the Soviet Union, Germany and the United Kingdom (and probably elsewhere) from the late 1920s onwards. Despite this, Mills didn’t reference any work in this field in his book. This led me to consider what Mills would or could have been aware of concerning these ongoing graphical sound activities at the time. He would most likely have accessed information through English language coverage of drawn sound techniques in US and UK newspapers, journals and magazines [N.B. UK news stories were often, as will be seen below, reprinted in the US press]. Therefore, it is likely he knew of the ‘painted sound’ work of Eric Allan Humphriss in the UK and his creation of a synthetic voice through painting waveforms on a soundtrack. This caused a sensation and garnered widespread press coverage across the world from 1931-1933. Likewise, Rudolf Pfenninger’s Tönende Handschrift (sound handwriting) received a good deal of English language press coverage from 1932-1936.

In Part 1 of my study of this press coverage I will focus on Humphriss and Pfenninger whose work dominated media reports on graphical sound until 1935; this covers the period running up to the publication of Mills’s 1935 book where very little was known outside the USSR about Soviet experiments in graphical sound. In Part 2 I will examine how press attention then refocused on news coming from the USSR about graphical sound research, with high profile examples of detailed coverage from 1935-1936 appearing in the US and UK (though the origins of Soviet graphical sound date back to 1929).

Importantly, this news coverage suggests that there was much wider general awareness of graphical sound techniques in the 1930s, whether in the USA, UK or elsewhere than usually appreciated. As Thomas Y. Levin demonstrates, there was also a good deal of coverage in France and Italy (and I have found further examples in other European countries) of German achievements in drawn sound. With this in mind, I also wonder how far John Cage had encountered this work through his research and general reading, which would have been a further strand of influence on his 1940 (but possibly later) The Future of Music: Credo lecture/article that referenced graphical sound.

Before moving on to examine US and UK media coverage of graphical sound in the 1930s, it’s worth noting that a key theme can be found in early to mid-twentieth century writing on the (electrical) future of music that has a direct relation to drawn sound techniques. The idea that sound could and should become a medium that can be painted or sculpted was a continual theme going back to the earliest years of the twentieth century. The implication was that, if this breakthrough was achieved, composers would have the same relationship to their musical materials as painters have to paint, or a sculptor to the medium they are working in. This would allow composers to bypass or disintermediate performers. This was important as the transmission loss of ideas and compositonal intentions, when an interpreter is needed to bring a composers’ work to life, was a constant concern for modernist/futurist writers in the period. The ability to ‘paint’ sound directly onto a medium would give the composer absolute control over how their music would be encountered and heard. Graphical sound processes appeared to be able to make this dream a reality, though writers such as Mills and Chavez emphasised a great deal of work and further technical development, over a long period of time, would be necessary to fully achieve this goal.

Eric A. Humphriss and the Synthetic Voice [1931]

Although graphical sound experiments had been taking place from the late 1920s, the first time widespread media coverage was given to the technique was with the ‘sensational’ story of how Eric Allan Humphriss had created a fully synthetic voice. This was achieved through the intense study of voice recordings on optical film soundtracks, and by Humphriss then painstakingly painting waveforms on a strip of cardboard to be transferred to a film soundtrack for playback. There are two periods where his innovative work caused flurries of activity in the press. Between February and May 1931 where newspapers around the world reported on a Daily Express [UK] [16-2-1931] article ‘Artificial Voices Made In A Film Studio’, and again from late 1932 to early 1933.

The Daily Express article, written by Cecil Thompson, is the most detailed and high-profile (published on page 1 and 2) description of Humphriss’s work, even though another 3 journalists also attended the painted sound demonstration at the London office of the Producers’ Distributing Company (an American film company). Thompson began

FOUR men sat in a darkened room in London yesterday morning and listened to words which had never passed through human lips - words spoken by a voice which never existed … It was not a spiritualistic séance. There was nothing supernatural about the phenomenon. The experience can only be described as the birth of the world’s eighth wonder - the creation of the "robot" voice.

When asked how the synthetic “robot” voice was constructed, Humphriss replied that it was made with ‘[f]orty feet of thin cardboard, a bottle of Indian ink, a mapping pen, and a reel of celluloid’. The process took him over 100 hours. Thompson studied the long cardboard strip given to him and described the painted markings as ‘a strip of zig-zag lines - rather like the record of an earthquake on a seismograph’. Humphriss explained

I chose the words I wanted the “robot” to speak, and dissected them into their various sounds - the ‘fffv' of ‘of,' for instance, or the ‘trrr” of ‘tremble'. One by one I drew them, through a magnifying glass, on my cardboard strip. Then I joined the strip together, with the sounds in their proper sequence [and] photographed it on standard celluloid film …

He then took the 4 attendees to a projection theatre to witness what had been achieved with this method. Thompson reported

There was silence. Suddenly a crackling noise started just behind it. The voice spoke. A deep bass voice it was, clear as a bell, sufficient to please the ears of any Oxford don. "All … of … a … tremble ," it said.

Thompson’s first reaction was that ‘[i]t was terrifying for the moment, almost horrible. I felt a tingle down my spine. I had heard a voice that was not a voice, words that had never been spoken’. For the listeners, there appeared to be something deeply uncanny about this voice from nowhere.

Humphriss then mulled over potential future developments. One of these was close to John Mills idea of the use of sound templates that could be combined to create complex musical tones. Humphriss suggested ‘a dictionary of sounds, which can be copied in a few moments, and made into long sentences’ could be used to shorten the process, perhaps with a ‘gigantic typewriter containing every sound which is needed in ordinary use, so that the voice can be put on a mechanical basis’. He also suggested musical uses. For example, he would be able to

create the perfect tenor. No human voice is perfect; even Caruso's had its faults. But what if you could take the voice of Caruso and eliminate these faults and emphasise its perfections? That will all be done with a few strokes of a brush or the tapping of key or two of the voice typewriter. Covent Garden will perhaps live to see "Tosca" played and sung by musicians who have never lived.

Pelletier (2009) indicates that the story gained widespread coverage when syndicated in various forms in the USA by the Associated Press and Central Press. The news stories I have found were also syndicated by the Canadian Press Service. On 16th February 1931 - the same day as the Daily Express article was published - the New York Times [via a ‘Special Cable’], the Columbia Daily Tribune [Missouri], the Albert Lea Tribune [Minnesota], the Daily Mail [Hagerstown, Maryland] and the Hamilton Spectator [Ontario] and other newspapers carried a short summary of the Daily Express story. On 19th March the Winnipeg Tribune published a more detailed article, again based on the Express story. Therefore, this initial account travelled quickly around the world. Whatever efforts were being made at the time with graphical sound processes elsewhere, these were eclipsed by Humphriss who appears to have been the first to make the wider public aware of the phenomenon of drawn sound.

In late 1932, Humphriss again drew attention to his work through stories of his latest achievement. A Central Press feature by A. John Kobler, Jr. reported

In a recent film Constance Bennett was heard by her admiring public to utter coyly the name of a fictitious British peer. Her public was fascinated by the way the name rolled from her tongue with just the proper intonation … But “Connie” never spoke that name. Neither did anyone else …

The truth is Humphriss had stepped in when the film-makers and distributors realised the original name used in the script was that of an actual British peer; this needed to be altered for legal reasons. In an interview undertaken for the Central Press article, Humphriss described how he had replaced the name using his synthetic voice technique; interestingly, there is also evidence that he had progressed with his synthetic musical experiments. Kobler wrote

When I spoke to Humphriss he pointed to another strip of film on his desk. He told me it was the world’s perfect voice. It wasn’t Caruso’s and it wasn’t McCormack. It was no one’s. This time it was singing … [he had] succeeded in making a throatless voice sing an entire octave. It is perfectly recorded - a bass now, but with a few strokes of the pen it can be a tenor or even a soprano.

This story was carried by many US newspapers (e.g. the Evening Independent [Massilon, Ohio] and the Morning Call [Allentown, Pennsylvania] in December 1932). Other articles appeared in the UK, and two have been found so far in Australia (the Sun News-Pictorial [7-1-1933, Melbourne] and the Brisbane Telegraph [1-4-1933]). Again, this demonstrates the wide reach of the painted sound process of E. A. Humphriss in the 1931 to early 1933 period. However, it appears that he made little, if any, further progress in this field, eventually moving on to the Viking Films production company where he worked as a film director (particularly on comedy and variety films) and managing director of the Viking Film facilities. In 1938 the Yorkshire Evening Post [18-6 p.7] reported that Humphriss had again used his ‘drawn speech’ skills for a Viking Films production, Take Off that Hat, that he also directed; he replaced a word in a scene ‘that did not seem right in the finished film’. He clearly retained a particular interest and expertise in sound recording and other technical film matters in his directing work, as reported by the Kinematograph Weekly [24-6-1943 p. 31]. During and after WW2 Humphriss and the Viking Films facilities in London became associated with the work of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, who moved their production base there after 1953 (Kinematograph Weekly [17-9-1953 p. 38]).

Rudolf Pfenninger and Tönende Handschrift (Sound Handwriting)

E. A. Humphriss may have been the first to draw public attention to graphical sound, but it was Rudolf Pfenninger’s work that had a higher profile over a longer period (from 1932-1936), based on a greater level of technical development and artistic achievement.

Rudolf Pfenninger was born on 25th October 1899 in Munich, Germany. Over his career, alongside his sound handwriting or hand-drawn sound work, he was also an animator, sound engineer*, draughtsman and film production and set designer. He studied drawing with his artist father Emil Pfenninger, and began experiments with a camera he had constructed for himself. There followed an apprenticeship as a set painter in the Munich Werkstätten für Bühnenkunst [Munich Workshops for Stage Arts]. From 1914 he worked with his father as an illustrator for Swiss botanist Gustav Hegi’s multivolume reference work, Illustrierte Flora von Mittel-Europa [Illustrated Flora of Central Europe]. During this period Pfenninger worked as a projectionist at various Munich cinemas, an experience that helped him to become familiar with a range of film technologies (optics, mechanics, electronics).

In 1921 U.S. animator Louis Seel hired Pfenninger to draw, paint, and make animated films for the Münchner Filmbilderbogen series. In 1925 he moved to a new job at the Geiselgasteig studios of EMELKA [Münchner Lichtspielkunst AG studios] where he worked on films including Zwischen Mars und Erde [Between Mars and Earth] (Dir. F. Möhl) [1925]. He pursued engineering research on new radio technologies, and developed and patented a number of improvements for sound recording technologies. In his laboratory work he began experiments in synthetic sound, or Tönende Handschrift (Sounding Handwriting).

Pfenninger studied the visual patterns of sounds using an oscilloscope and by 1929 was able to identify and reconstruct waveforms for specific tones. He used the newly available optical film soundtrack to test his experimental results. He drew ‘sound designs’ onto a strip of paper that was then photographed onto a film soundtrack. As with the Humphriss method, the sounds produced had no prior real world existence before Pfenninger drew them. They were ‘tones from nowhere’ as Levin outlined. Levin indicated that

the first films that Pfenninger made for EMELKA in late 1930 with an entirely synthetic sound track - an extremely labor-intensive task that involved choosing and then photographing the right paper strip of sound curves for each note - were his own undersea animation, Pitsch und Patsch, and a “groteskes Ballett” film directed by Heinrich Köhler and entitled Kleine Rebellion.

Levin goes on to explain that Pfenninger’s films were first publicly exhibited at the EMELKA studios to journalists in late spring 1931, with German newspaper coverage favouring Pfenninger’s achievements over those of Humphriss in London. The first public demonstrations came a year later through the exhibition of a filmed interview and demonstration featuring Pfenninger, and a number of short films utilising the technique. The films premiered at the Munich Kammerlichtspiele [19-10-1932], and the following day at Berlin’s Marmorhaus cinema.

Levin discusses in depth the range of responses to the screenings in the German press, but the aim of this article is to see how far Pfenninger’s work reached English speaking audiences in the period - as Levin notes, British newspapers and journals in particular took a keen interest in Pfenninger’s work.

The first British news story can be found in The Times [23-11-1932] in a news item, ‘Talking Films With No Talkers’. On the implications of Pfenninger’s method for film economics and music, the Times Munich correspondent wrote

The immediate advantages claimed for Herr Pfenninger’s invention are a great saving in the costs of production through the simplification of the process of sound-film manufacture; and the capacity to produce musical notes having a degree of clearness and purity which cannot be obtained through the medium of any musical instrument.

More high profile coverage ensued, with a full-page feature in the Illustrated London News [24-12-1932] featuring four images of Pfenninger at work in his studio. The article reported

In addition to being able to draw the vibratory shapes of normal sounds, Herr Pfenninger is also able to draw new sound-forms of his own, weird and fantastic noises “non-existent in nature.” Moreover, he states that by his method, he can ‘touch up’ the voice of a film artist who, although a fine actor, may possess but poor vocal powers.

The latter claim seems directed at the work of Humphriss, perhaps suggesting Pfenninger can go much further than Humphriss had been able to at that point.

Also in December, news of Pfenninger’s sound handwriting technique had begun to be reported in the US. The Springfield Evening Union [Massachusetts 8-12-1932 p.11] reported on a recent article in the Berlin illustrated news publication Die Woche providing an overview of Pfenninger’s ‘sound-writing’. Interestingly the article also consulted Dr. A. N. Goldsmith, until recently the vice-president and general manager of RCA, and who had written on electronic music in the period. Goldsmith indicated that there had already been similar experiments in the US and UK, and even if Pfenninger’s method had improved on that of others, he wondered why anyone should wish to produce such a synthetic product when ‘the natural state’ of the voice is cheaper and better. However, Goldsmith did see some potential for the composition of music, stating

new musical tones may and have been produced, totally unlike anything that has previously existed. That is a field in which experimenting may have a profitable result. New tones are interesting and entertaining because they present new architectural creations in sound.

Further regional US coverage in December 1932 (The Echo [Buffalo, New York] 29-12 p. 4]) and January 1933 (The Springfield Daily Republican [Massachusetts 1-1 p. 42]) was followed by a detailed New York Times [22-1-1933] article by Waldemar Kaempffert, ‘The Week In Science: Unplayed Music In Films’, that mistakenly printed a photograph not of Pfenninger but of his drawn sound compatriot, Oskar Fischinger**. Kaempffert reported on the (negative) responses of witnesses who had heard Pfenninger’s reproduction of Handel’s Largo.

German technicians are delighted with the underlying principle applied by Pfenninger. On the other hand, the musical public, which cares little for the elegance of technical methods and is interested only in results, thought that Pfenninger’s synthetic music sounded like bad broadcasting rendered audible by the worst of the old loudspeakers.

On the 29th January, the New York Times then recycled the 23-11-1932 London Times article, providing a more neutral commentary on the subject.

Back in the UK, on 18-2-1933, radio listings for the German Heilsberg transmitter in Eastern Prussia listed a programme at 5.00-5.30 pm; ‘Musical handwriting, an interview with the inventor, Rudolf Pfenninger’. Two days later a writer in the Nottingham Evening Post [20-2-1933 p. 6] wrote that he had heard the broadcast, and of Pfenninger’s music he stated ‘[i]t was a kind of staccato music, played very quickly, and was very pleasant on the ear.’ In the early days of radio listening, searching out foreign broadcasts from continental radio listings was a common activity.

On 3rd February the UK magazine Wireless World published a full-page illustrated feature on Pfenninger, ‘Synthetic Sound: Voices from Pencil Strokes’, by Herbert Rosen. In a semi-serious article, Rosen remarked

Nowadays, with increasing skill, [Pfenninger] can even improve on the product of us poor imperfect humans, smoothing and polishing his curves until his results give an inhuman perfection of articulation which even a B.B.C. announcer can never attain!

In the USA, Pfenninger continued to be referenced in news items, to the extent that a Harold D. Detje ‘Be Scientific [With Ol' Doc Dabble]: Paint Brush Music’ cartoon was widely published in regional newspapers across the country in March 1933.

In July 1933, Wireless Magazine [UK] published a 3-page illustrated feature article, ‘Making Sounds from Drawings’, by artist-photographer Rene Leonhardt. This again covered Pfenninger’s techniques, but in more detail than in many previous articles, and also briefly considered László Moholy-Nagy’s experiments with ‘drawn gramophone records in the mid-1920s, and Oskar Fischinger’s ‘sound ornaments’ method. Leonhardt emphasises that Pfenninger does not wish to simply ‘reproduce graphically the tones of well-known musical instruments such as the violin, the piano etc. On the contrary, his aim is to construct music of an entirely new timbre.’

Autumn 1933 saw another prestigious article on Pfenninger, this time in the British Film Institute’s Sight and Sound magazine [UK]. The writer Paul Popper, however, seems to have used Rene Leonhardt’s Wireless Magazine article as a ‘template’, with many close similarities in the text (and Popper’s article later appeared again in Kinematograph Weekly [11-1-1934 p.119]). A notable claim in the article was that Pfenninger had described the possibility of perfecting a method

whereby sound waves can be “written” mechanically. It is said that he is at present constructing an apparatus like a typewriter which, instead of letters, will set together wave signs in succession.

This idea is almost identical to that proposed by Humphriss in his 1931 Daily Express interview, where he stated he would next like to develop a

gigantic typewriter containing every sound which is needed in ordinary use, so that the voice can be put on a mechanical basis.

Pfenninger’s films were finally screened in Britain at a meeting of the British Kinematograph Association in January 1934. The Times [9-1] reported in an article, ‘Synthetic Sound: Musical Demonstration in London’ that Capt. West ‘introduced a number of short films, made by Herr Pfinninger (sic.), of Munich, and set to music which had its origin neither in the human voice nor in any instrument.’ The article continued

Handel’s “Largo” was played, ballets were performed, cartoons had their full accompaniment, guns were fired off, but the various tunes and noises ere created by some drawings that Herr Pfininger made on strips.’

Capt. West was in fact Arthur Gilbert Dixon West, a major figure in British communications, who had worked at the early BBC, HMV, Baird Television Ltd. and Cinema Television Ltd. News of the demonstration also reached Canada, where the Province newspaper [Vancouver 10-2-1934] described Pfenninger as

a sort of Walt Disney of sound. Instead of bringing life to cartoon figures drawn by himself, he draws sound variations. These are translated into music that nobody had heard until they are animated into activity by the film projector.

The Province then considered the implications of Pfenninger’s work for the future of music, and again, in a manner very similar to John Mills prophecies in his 1935 book A Fugue in Cycles and Bels, the writer stated

If this invention is followed to its logical conclusion the composer of the future will be independent of voices and instrumentalists, for he will be able to combine them all in hand-written music upon film direct for the screen.

On 14th November 1934, Capt. West again demonstrated Pfenninger’s synthetic sound techniques for a Television Society meeting at the Gaumont-British theatre in Wardour Street, London, with screenings of Pfenninger’s short films and his filmed interview. Captain Ernest H. Robinson in the Observer [25-11-1934 p. 13] wrote

Whether synthetic sound will have any application beyond providing exciting and amusing noises for the talkie cartoon remains to be seen. As demonstrated to a large audience last Wednesday it is certainly a very remarkable achievement of painstaking genius.

Soon after in January 1935, Practical Television [UK] ran a page and a half illustrated article, ‘Sound By Synthesis: How Sound Is Made By Artificial Means’, that again outlined Pfenninger’s methods, and reflected with some technical and musical insight on the authors recent experience attending the Television Society demonstration.

“Drawn Music,” giving classical melodies, was recently heard by the writer, and although in no way jarring to the ears, it seemed as if the sound lacked something to give it a really pleasing effect. This was no doubt due to the absence of echo, but it must be remembered that the development work on synthetic sound is of comparitive recent growth, and many improvements will be effected. The Sound patterns seen on the film were extremely weird and nearly all of triangular formation. This was no doubt done to produce the harmonisc together with the fundamental. In addition, sound intensity was brought about by fine grey shading, and with complex sound expressions as many as five or six sound track patterns were interleaved one with the other … when the whole technique of “unborn sound” is more thoroughly understood it will surely open up new ideas of real value.

Although by early 1935 there appears to be a general and growing awareness of Pfenninger’s sound handwriting method, by this point he had already abandoned his work. Levin indicates the reason for this by explaining

As it turns out, the five films in the Tönende Handschrift series—the first results of Pfenninger’s experimentation with synthetic sound—were also his last. In a 1953 interview Pfenninger explained the lukewarm response [in Germany] to his invention in the early 1930s as follows:

“The time was not ripe, my invention came twenty years too early.” Or perhaps too late: only a few years later Pfenninger’s films would be designated “seelenlos und entartet” (soul-less and degenerate) by the Nazis, and thus, not surprisingly, work in this domain effectively came to a halt.

Despite this, Pfenninger continued to work in the German film industry, as a production and set designer in the Munich Geiselgasteig studios (formerly EMELKA)., and was appointed Chefarchitekten [chief architect] at the studios in 1939. He worked on 23 films in this role from 1939-1952. In later years he illustrated advertising films, and died in June 1976 in Baldham, Germany.

In September 1935, in a The Witness [Ontario 4-9-1935 p. 7] article ‘Synthetic Music’, it is notable that though Pfenninger’s achievements are acknowledged, the writer focuses more fully on the achievements of graphical sound artists from the Soviet Union - in particular ‘N. Voinov’ and ‘E. Sholpo’ who until this point had no real profile outside the country. This is despite the fact they had been working on drawn or graphical sound techniques since the late 1920s. This was soon to change. Part 2 of this article will examine how a growing awareness of Soviet work in this field developed from 1935 onwards.

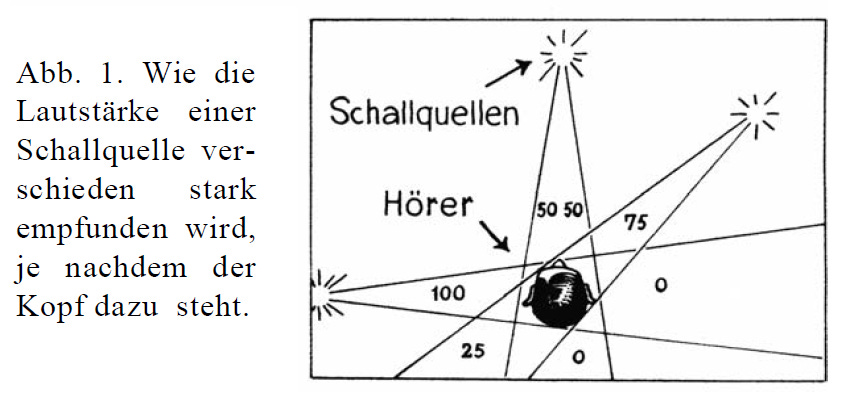

* In the 25th January 1931 issue of the German magazine Funkschau, Rudolf Pfenninger demonstrated his broader sound engineering expertise when he contributed a technical article on ‘Räumliches Hören od. Schallperspektive? Ein Vorschlag: Die Echomaschine’ [Spatial Hearing or Sound Perspective? A Suggestion: The Echo Machine]. The article discusses how ‘flat’ sound transmissions and recordings have begun to be modulated in London and Munich by ‘echo chambers to superimpose reverberation effects on the sound generated in small rooms’.

Pfenninger described a technical method, an echo machine, where he could achieve more diverse reverberation effects, and more control over them than was possible through an echo chamber. The echo effects would extend to those ‘created in the mountains and forests’, with the method described having some similarity to later tape echo machines.

** Oskar Fischinger had comparatively little English language press coverage in the early 1930s - this is why I have particularly focused on Pfenninger in this post. However, a full-page feature article by Dr. Alfred Gradenwitz outlining aspects of Fischinger’s work did appear in Amateur Wireless (UK) in November 1932, with the same article (with light editing) also appearing in Hugo Gernsback’s Radio Review and Television News (USA) in the January-February 1933 issue. The article, ‘Sound From Drawings’ discussed Fischinger’s use of geometric ornaments photographed on the 3mm film soundtrack band, and noted the future potential for complex, multi-track orchestral compositions using this process;

While several ornaments can be traced beside one another even on these narrow bands, incomparably greater possibilities will result from a utilisation of the full width of the film, and musical composers are likely to avail themselves of these possibilities. In fact, they will be able on such films not only to hit any pitch with the utmost accuracy but to represent, beside one another, the characteristic timbres of all the instruments of which an orchestra is made up. The composer's work is by this new draughtsmanship, recorded in far greater detail than by the usual system of note writing - all personal, individual characteristics, usually left to the conductor's interpretation, thus being faithfully registered.