Lee de Forest and his Orchestra of Audions

The audion vacuum tube and early developments in electronic music

It is widely acknowledged that Lee de Forest's 1906 invention - the three-element vacuum tube that he called the 'audion' - was a key development in the history of electrical engineering that paved the way for the electronic revolution of the twentieth century. However, it is also generally understood that it required further refinements by Edwin Howard Armstrong and others to enhance the capabilities of the original audion for electronic signal detection, amplification and oscillation that enabled the successful development of radio, television and many other electronic technologies. These new technologies included new musical instruments such as those developed by Lev Termen/Leon Theremin and Maurice Martenot among others. However, of the early innovators in electronics, only Lee de Forest seems to have taken seriously the potential of the audion triode for the production of audible musical tones, resulting in an experimental musical instrument that he presented to the public in 1915. This article will examine de Forest’s work in this area as well as the influence it had on future innovators.

On 4th October 1915 the New York Times hyperbolically reported that the previous day Lee de Forest announced ‘that he had made electric lights play for him music surpassing far the best efforts of the best orchestra’, with de Forest stating

Now that the attention of the public has been drawn to the astonishing use of the incandescent lamp, not only as a receiver in transcontinental wireless telephony, but as a generator of power necessary to transmit the voice in the first place, it may be interesting to know that this incandescent lamp, or audion, has another entirely different field of utility - that of producing sound or music. Music from light - that, in a word, is the latest magic of the lamp.

Just over two months later, on 11th December 1915, the New York Times wrote that ‘Lee de Forest revealed last night for the first time to the public a new use of his audion, in the main auditorium of the Engineering Building, at a concert of electrically operated musical instruments, under the auspices of the National Electric Light Association and the New York Electrical Society’. The other electrically operated musical instruments demonstrated were the Lyrachord (a piano that also creates organ-like tones through the action of electrical magnets on the strings). The Autopiano, the Grafonola Grand, the Solo Apollo and the Lafarque Dynachord. de Forest in introducing his audion instrument emphasised that he was only able to perform a short demonstration with a limited number of timbres. The New York Times observed that

Not only does Mr. de Forest detect with the audion musical sounds silently sent by wireless from great distances, but he creates the music of a flute or violin or the singing of a bird by pressing a button. The audion … now not only detects electrical waves from great distances, but produces a sensation which, acting through a magnet on an ordinary telephone receiver, gives off music. The tone quality and the intensity are regulated by the resistance in the lamp and by the induction coils.

de Forest indicated that the audion could potentially produce a wide variety of tones, from ‘perfectly sustained notes’ to the ‘shrill warble of birds’, the ‘staccato effects of drum beats’, and notes closely resembling ‘bowed strings’. He was keen to emphasise that Thaddeus Cahill’s huge, building sized Telharmonium instrument had, with some difficulty, also been able to produce such sounds, but he could achieve this ‘with only one audion’.

In an article in Popular Science Monthly [January 1916, p. 71-73] George F. Worts agreed, writing

The idea of converting the silently flowing electric current into strains of the most bewitching music is not entirely new. Many readers will recall the telharmonium, which was built at great cost several years ago and with which electrical concerts in the home were prophesied. But the telharmonium required dynamos of such variety and size that it was eventually given up because of the prohibitive cost.

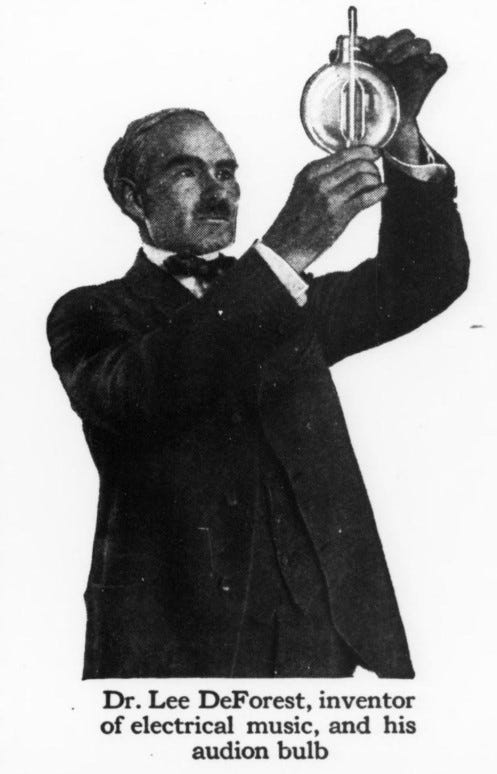

Despite this acknowledgement of Cahill’s earlier work, Popular Science Monthly slightly bafflingly captioned an accompanying image of de Forest with the title ‘inventor of electrical music’!

Around this time de Forest wrote in some detail about his experiments and experimental audion instrument in the Electrical Review and Western Technician [13-11-1915, p. 908-909], The Electrical Experimenter [December 1915 p. 394-395], and Popular Mechanics [February 1916, Vol. 25 No. 2, p.193-199]. The text of all the articles covered very similar ground to the initial New York Times report in October (suggesting a single piece of writing was used as the basis of all the articles), but it was in The Electrical Experimenter where the ideas de Forest proposed were also strikingly visually interpreted.

In the feature titled ‘Audion Bulbs as Producers of Pure Musical Tones’, Lee de Forest described the progress of his findings over previous years, and possible ways forward to create workable electrical musical instruments. He outlined how

While working on my experiments in developing the audion as a wireless telephone detector … I made the discovery years ago that when the circuits of the audion were connected in a certain way a clear, musical note was heard in the telephone receiver, which was connected in one of these circuits. The quality of the note was very beautiful, and I found after a little experimenting that I could change this quality of [timbre] into a great variety of sounds, imitating, for example, the flute, oboe, cornet, stringed instruments and other sounds which, while pleasing to the ear, were quite unlike those emitted from any musical Instrument with which we are familiar. The pitch of the notes is very easily regulated by changing the capacity or the inductance in the circuits, which can be very readily effected by a sliding contact or simply by turning the knob of the condenser. In fact, the pitch of the notes can be changed by merely putting the finger on certain parts of the circuit or even by holding the hand close to parts of the circuit. In this way very weird and beautiful effects can be obtained with ease … I found it was a comparatively simple matter to arrange a crude scale similar in function to that of an organ, with switches in place of the ordinary keys, so that by pressing certain keys I could cut out, or in, more or less inductance or capacity or resistance, thus changing the notes emitted from the telephone receiver at will.

The article included a circuit diagram that outlined the method that de Forest had explored in his experimental instrument.

de Forest then went on to explain how his initial apparatus could be ‘upscaled’

At the present time I am using one bulb for an octave on the musical scale, with the arrangement of keys and switches such that from this one bulb I can produce the notes of that octave by pressing the appropriate keys. For the next octave another bulb is used, and so on. The output of all these bulbs is made common to one set of telephone receivers or loudspeakers, so that the total energy in the form of sound is that of all the bulbs which are operating at any one time.

Central to de Forest’s work was a keen and passionate interest in music, particularly opera, and it was this that prompted him to progress down this investigative route:

Although not a musician myself, I have always been exceedingly fond of music. The idea of producing beautiful musical tones by an entirely new method unknown to all our great composers and perhaps offering to future composers new fields for their genius, has truly captivated me. In the next twelve months I hope to be able to produce an instrument which will be far enough perfected so that I can turn it over to musicians to work out the thousand and one details of musical perfection which such men alone are capable of introducing.

Hugo Gernsback, editor of The Electrical Experimenter as well as the ‘father’ of US science fiction, writer, magazine publisher and pioneer of electronic music himself, commissioned an illustration of what de Forest’s ‘Audion piano’ could eventually look like.

de Forest explained the features of the illustration noting

The various controlling handles are observed on the front of the piano, and the music is emitted from the large horns on top of same. A storage battery of small size will supply sufficient current for this wonderful instrument, and the feet might be utilized in assisting to effect variations in the audion bulb circuits. Each bulb is capable of producing an octave or eight notes. The large keyboard similar to those used on organs is well suited to this instrument, with which it will become possible to reproduce imitations of any band, orchestral or stringed instrument, etc. Extra oscillator bulbs for emergencies for use in case one should break, are seen lying on the stand at the left. It should be thoroughly understood that music produced by such an instrument as this is much purer in every way than that produced by any other type of musical instrument now known to the art and, moreover, the music is electrically produced in contradistinction to that produced by the usual musical pieces which yield sounds mechanically, so to speak.

However, despite de Forest’s (and Gernsback’s) dramatic visualisation of the audion piano, de Forest’s attention was soon drawn away from electrical music to further developments in radio broadcasting, and by 1921, to ‘Phonofilm’ or a sound-on-film process. Between October 1921 and September 1922 de Forest relocated to Berlin and met the German inventors Josef Engl, Joseph Massolle and Hans Vogt, and researched European sound film systems and wider developments in European electrical engineering research. After demonstrating his new phonofilm system in Berlin, he returned to the USA, and in November 1922 established the De Forest Phonofilm Company in New York. Further demonstrations of his new system followed in 1923.

However, in the middle of all this activity, de Forest in 1922 once again returned to his work on the audion as a musical instrument. What prompted this is not known, but it is potentially the case that while in Europe he had become aware of the early patents of Martenot and Theremin, and felt on his return to the USA that he had to stake a claim on this area of electrical musical development, one that he had pioneered at least seven years earlier. In November 1922 in the magazines Literary Digest and Popular Radio [USA] and in January 1923 in Popular Wireless [UK], an article by de Forest was published titled ‘My Orchestra of Audions’.

In the article he reiterated

There is one phase of audion application in which I have always had a deep personal interest. This application does not lie in the field of practical utility, but in the world of art and imagination, in the province of music.

For, in addition to its many other magic feats, the audion may be used to produce musical harmonies far more beautiful than those of any musical instrument yet devised.

Music from the audion! That is the theme which I suggest to those who are interested in the undeveloped possibilities of the vacuum tube.

de Forest began by sketching out the early work he had done culminating in the public demonstration in 1915, and then explained the basis of the musical tones he had produced, stating

vacuum tubes can be made to oscillate not only at the high radio frequencies, but also at the much slower audio frequencies. This, indeed, is just what the tube does when it goes wrong temporarily and howls into the telephones of a radio receiving set. It is oscillating at a comparatively low frequency, a frequency within the audible range. All that we have to do to bring this about artificially is to arrange a partial feedback circuit containing the proper inductances and capacities to produce just the frequency, that is, the tone, which we wish. The electric oscillation thus produced, being already of audio frequency, requires merely to be fed into a telephone or loudspeaker in order to give us ordinary sounds in the form of a musical tone.

Next he outlined how the ‘audion organ’ can increase the tonal resources available to composers

Musical tones differ among themselves in three qualities: pitch, loudness and quality. The pitch is simply a matter of frequency; the greater the frequency, the higher the pitch. Loudness explains itself; tones may be either very strong and loud, or very faint - or anything in between. Both of these two characteristics of a tone are fully controllable in the audion organ; pitch, as I have explained, by varying the frequency of the electric oscillation, loudness by varying the input of energy with a resistance or in any other convenient way.

But the third characteristic of tones, the tone quality, the audion organ also permits us to control; and it is this, I imagine, which will be of the most interest to the professional musician.

The differences in the sound of the various musical instruments are due almost altogether to differences in the quality of their tone. Middle C of the piano has a pitch or frequency of 262 vibrations a second. This same note played on a violin or on a clarinet or on a French horn has exactly the same frequency, 262 a second. Yet the notes from these different instruments do not sound alike …

All ordinary musical tones contain certain overtones superposed on the pure tones. These overtones are tones of higher pitch, that is, of higher frequency, which are sounded at the same time as the pure tone and blend more or less completely with it. The overtones produce little bumps and hollows, little kinks, in the sine-wave of the pure tone. Or they displace the maxima and minima of the wave, so that the original sine-wave is no longer exactly even and symmetrical. In electrical language they "distort the wave of the sound."

This distortion is what produces tone quality …

Now all of these variations of tone quality are obtainable - and controllable - with the audion organ. The musical audion may be adjusted so that its primary tone is absolutely pure, a perfect sine-wave. Or this primary tone may be altered merely by distorting the electric circuits, so as to cause any desired change in the quality of the sound. It may be made to counterfeit the piano, the violin, the 'cello or the horn, or may be distorted into any sort of sound - musical or grotesque.

In considering the implications of this and other new electrical instruments for the orchestra and future composers, de Forest argues

The flexibility of the orchestra, its resources of tone color, or expression or emotional portrayal, while very great in comparison with the piano or with any other single instrument, is still far from being as complete as is possible in theory …

I believe that the musical audion will soon be able to widen greatly even the great flexibility of the orchestra. Audion tubes can play notes of any pitch; even, if necessary, notes several octaves above the piccolo or the violin harmonics. And they can play all of these notes, high or low, with any desired tonal quality; with the quality of horn or oboe or 'cello, or with new qualities not yet known or used.

What a resource for the composer! What possibilities of new orchestration, of undreamed of harmonies and melodies, tone colors and emotional effects!

In the audion we shall have an instrument suitable for home entertainment as well as for furnishing music to a big auditorium. And music thus produced may be taken up again by the audion, this time for broadcasting, and finally received by the countless other audions of receiving sets throughout the world. The musical audion, the radio transmitting audion and the receiving audion, each one doing its share toward the enrichment of life!

As such, de Forest’s intervention through his 1922 article is an elaboration on his previous pronouncements in 1915, and provides a clearer understanding of the benefits and qualities of ‘audion organs’ for future music making. However, there is no indication that de Forest had sustained his earlier technical experimentation, though there is evidence in both articles that he had constructed a rudimentary multi-octave ‘Audion piano’ in his laboratory by 1915.

After 1922 Lee de Forest made no further progress in achieving his desire to see the construction of electrical instruments that enhanced and expanded the musical resources of musicians and composers. Clearly Leon Theremin, Maurice Martenot, and Jorg Mager in Germany were already working along similar lines to those suggested by de Forest, and by 1927-28 their instruments began to be presented to a wide audience outside of their laboratories at exhibitions and on concert stages.

However, in 1924, Marcel Tournier, a Professor at the Ecole Municipale de Physique et de Chimie industrielles in Paris had designed an ‘orgue électrique’ [electric organ] that was exhibited at the Paris Radio Exhibition, and had some similarities to de Forest’s ‘audion organ’.

Radio News [March 1924 p. 1239] reported that

One of the most interesting features of the Paris radio show was the exhibition of an electric organ employing the well-known and greatly used vacuum tube. One vacuum tube is used for each note of the organ and is adjusted so that when its key is depressed, it will oscillate at a definite frequency or period of vibration. The music from an organ of this type is said to be very beautiful. The inventor, Mr. Marcel Tournier, can be seen at the side of the "vacuum tube" organ. The piano part was constructed by the well-known firm of Gaveau.

Although working on the same principle as de Forest’s ‘audion organ’, Tournier had instead dedicated a vacuum tube to each musical note rather than one per octave - 22 in total. Whether Tournier had been inspired by de Forest’s work, or whether he had independently developed his instrument - as had Theremin, Martenot and Mager and others - is not clear. In fact, very little is currently known about this instrument at all. In the French publication Recherches et Inventions [15-2-1924 p. 395] the instrument is briefly described as an electric organ whose ‘sound-emitting system is an electric tube oscillator mounted on a soundboard’. In Le Génie Civil [26-3-1927 p.6], Marcel Tournier and Gabriel Gaveau were by 1927 instead working on the ‘Pianocanto’ - an electrical device that could be fitted to any piano that allowed the vibrations of the strings corresponding to the octaves to be maintained, with effects reminiscent of the organ or harmonium. There is no evidence Tournier and Gaveau continued with their earlier 1924 invention, and yet it was exhibited to the French public before the instruments of other French electronic music pioneers such as Armand Givelet and René Bertrand.

In summing up Lee de Forest’s role in the development of early electronic music, we can say that his ideas, mediated through patents, newspapers, and engineering and radio magazines must have had a relatively wide reach and an impact of sorts on the motivated and interested audiences of such publications. Many of the arguments and insights in the de Forest articles included here were common by the 1920s, where modernist and ultramodernist composers and musicians often discussed new musical resources that mechanical and electronic innovations could bring to music. However, de Forest may well have had a wider audience for his ideas than those writing in specialist journals such as Modern Music, and the fact he concerned himself with these issues from as early as 1912, before publishing his thoughts in 1915, suggests he was in many ways ahead of others in his speculation and experimentation. Clearly through the audion he also provided one of the key tools through which radio experimenters during World War 1 and after discovered the audible oscillations that were later manipulated and became the basis of many early electronic music instruments.